This article introduces Git fundamental knowledge including branch, fork, stash, merge, rebate. It explains major conceptions of Git branching model and workflow for each commands. These commands are required for next posting - best practice for team development via Git.

Outline

- Basic commands review

- set up git

- create local repository

- stage file(s)

- commit file(s)

- sync remote repository and local repository

- display git information

- discard changes

- Branch

- Introduction

- Workflow

- Fork

- Introduction

- Workflow

- fork vs clone

- fork vs branch

- Stash

- Introduction

- Workflow

- Merge, Rebate, Squash

Basic commands review

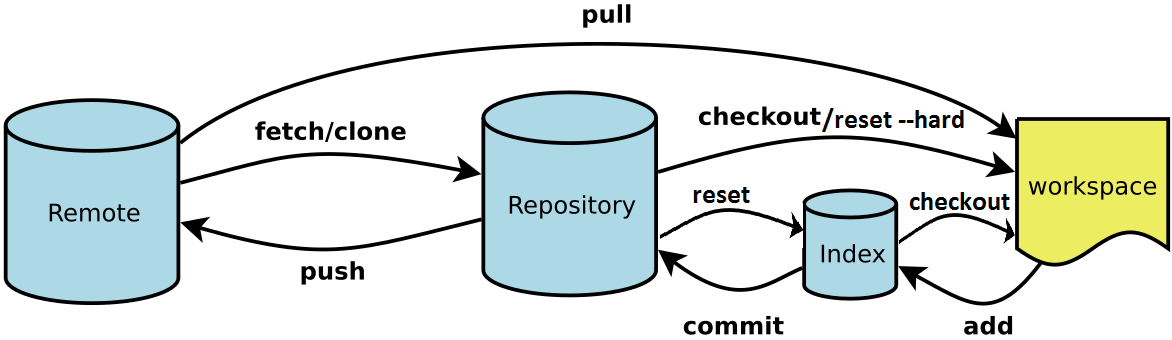

This is the git model:

Remote represents the remote repository

Repository is the local repository

workspace is the active branch we currently working on

Index is the staging area

Here are some basic Git commands:

Setup git

display git configuration

git config --list

edit git configuration

git config -e [--global]

setup user commit information

git config [--global] user.name "Andy Feng"

git config [--global] user.email "andy@email.com"

Create local git repository

Setup new git repository

mkdir new-repository

cd new-repository

git init

touch readme

git add readme

git commit -m "first commit"

git remote add origin https://github.com/new-repository.git

origin is an alias of remote repository.

git push -u origin master

master is the name of main branch in local repository it is equivalent to

git push -u origin/master master

Setup existing git repository

cd existing-repository

git remote add origin https://github.com/existing-repository.git

git push -u origin master

Clone a remote repository

git clone https://github.com/existing-repository.git

Create upstream tracking between remote branch and local branch

git branch --set-upstream-to origin/master master

Stage files to Index

stage specified files

git add [file1] [file2]...

stage specified directory

git add [dir]

**stage all files **

git add .

git add -A

delete specified files and stage them

git rm [file1] [file2]...

Commit files to local repository

commit all staged files to local repository

git commit -m [message]

commit specified staged files to local repository

git commit [file1] [file2] ... -m [message]

display all diff information of commits

git commit -v

Sync remote repository and local repository

Pull all remote changes

git fetch origin

origin is the name of remote repository. As a convention, we usually name it as

origin

Pull all remote changes and merge into a local branch

git pull <remote-branch> <local-branch>

e.g. git pull origin master

Push changes of a local branch to remote repository

git push <remote-branch> <local-branch>

Push all local branches to remote repository

git push <remote-branch> --all

Display git information

Display all changed files before commit to local repository

git status

Display the difference between workplace and Index

git diff

** List git commits **

Get the commit history of current branch

git log

Get the commit history of recent n commits

git log -n

Get the commit history and all files of current branch

git log --state

search git commits

git log -S <keyword>

Display the changed content of commit

git show

git show <commit>

display a specified commit

Display all configured remote repositories

git remote -v

Discard changes

Restore files to Workspace

Restore specified file from staged area (Index)

git checkout <file>

Restore all files from staged area

git checkout .

Restore from committed files

git checkout <commit> <file>

restore operation still keeps the staged or committed files. But the same files will be overwritten by the restored ones and new changes of files will lose. Status of file is not changed for this operation.

Reset files from commits

Reset specified file from local repository to staged area (Index) until last commit

git reset <committed-file>

Reset from local repository to staged area until specified comit

git reset <commit>

Reset both staged area and workspace until last commit, all changes in workspace lost

git reset --hard

Reset both staged area and workspace until specified commit, all changes in workspace lost

git reset --hard <commit>

Reset to specified commit, and create a new commit for this reset

git revert <commit>

Reset to specified commit, and keep all changes in workspace

git reset --keep <commit>

reset operation essentially rollbacks files from previous commit status. by default, only the status of file is changed from committed to staged. New changes of files still keep. –hard option: both the status of file is reset and the changes of file lose –keep option: only reset the status of file but keep the changes of file

e.g. discard all local changes and reset master branch:

switch the repo to the master branch: git checkout master

pull the latest commits: git fetch origin

reset the repo’s local copy of master branch to match the latest version: git reset --hard origin/master

Branch

Introduction

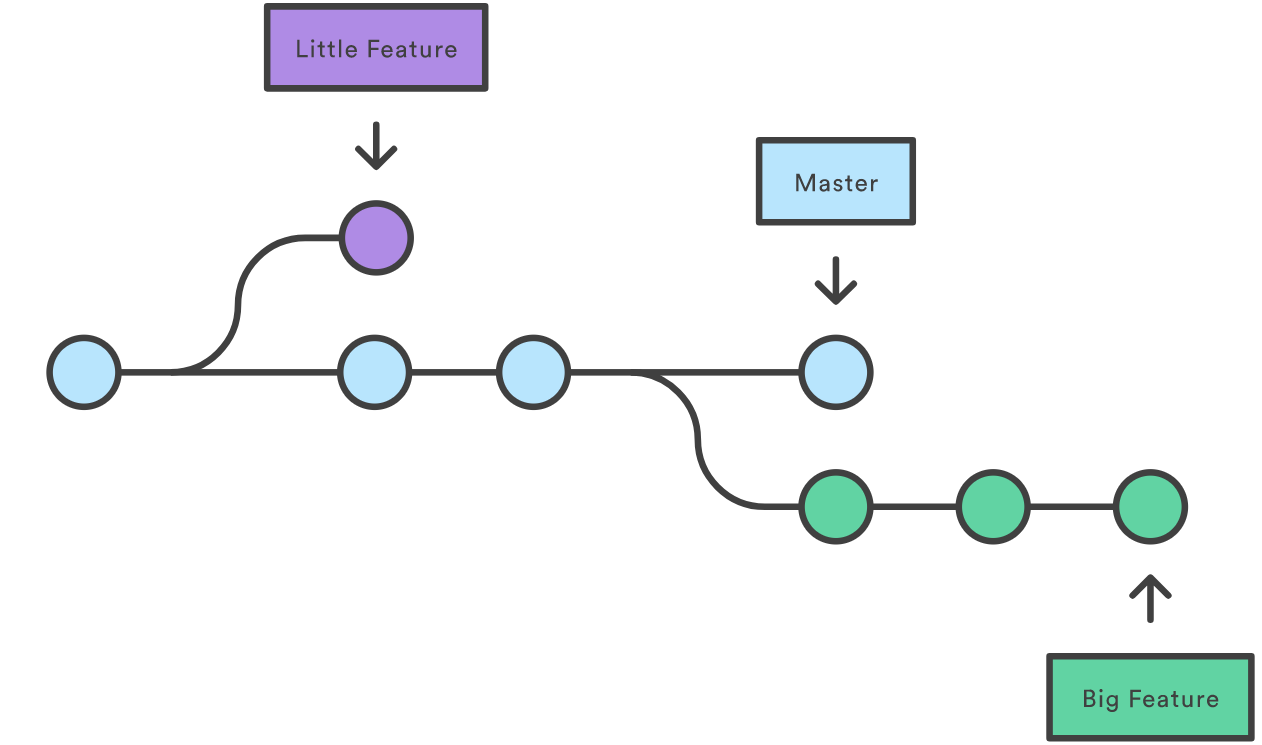

A branch represents an independent line of development. When a git repository is created, a default master branch is created. We can create new branches anytime.

In Git, branch is a part of our everyday development process. When we want to add a new feature or fix a bug — no matter how big or how small — we spawn a new dedicated branch to encapsulate our changes. Then, we clean up the feature’s history before merging it into the main branch.

The benefit is, branch makes sure that unstable code is never committed to the main code base and keep development activities organized.

For example, the diagram above visualizes a repository with two isolated lines of development, one for a little feature, and one for a big feature. By developing them in branches, it’s not only possible to work on both of them in parallel, but it also keeps the main master branch free from questionable code.

Here are some common commands:

List all branches in local repository

git branch

List all branches in remote repository

git branch -r

List all local and remote branches

git branch -a

Create a new branch called <branch>. This does not check out the new branch.

git branch `<new-branch>

Switch to another branch

git checkout <existing-branch>

Create and switch to another branch

git checkout -b <new-branch>

-b flag tells Git to create the branch if it doesn’t already exist.

Delete a branch

git branch -d <branch>

This is a “safe” operation in that Git prevents you from deleting the branch if it has unmerged changes.

git branch -D <branch>

This is a “force” delete operation and it will permanently delete the specified branch, even if it has unmerged changes.

Rename the current branch to another name <new-branch>.

git branch -m <new-branch>

push a branch to remote server

push a branch to remote server

git push origin <branch>

push “master” branch to remote server

git push origin master

delete a remote branch

git push origin --delete [branch-name]

Workflow

Here is how Git branching model works:

-

create a new branch for each new feature/fix

git checkout -b <new-branch> -

work on it

-

merge it back to Master when done

git checkout mastergit merge <branch>fix conflicts if has any

git commitor

git merge <branch> master -

push master branch to remote repository

git push origin master -

delete the feature branch

git branch -d <branch>

Fork

Introduction

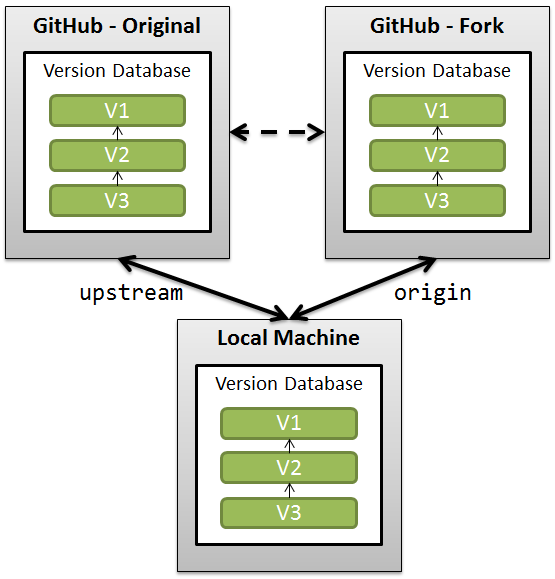

Fork represents a complete copy of a repository. It creates a complete server-side repository copied from the original repository and allows us to freely experiment with changes without affecting the original project.

There are tons of public repositories over Internet. Usually, we are not the direct contributors. Fork offers an opportunity for us to engage in contribution. Fork allows us to clone these public repositories and create our own server-side repositories from them. Then, we can work on forked repositories exactly like we contribute our own repositories. Later on, we can initiate pull requests to original repositories and notify the owners to accept our contributions. Overall, fork allows the maintainer to accept commits from any developer without giving them write access to the official codebase.

In forking workflow, the original repository is typically named upstream and runs independently. The forked repository (typically named origin) and local cloned copy is runs independently too. origin 和 upstream 并不是 Git 软件本身的硬性规定,而是 GitHub 社区多年来形成的约定俗成(Convention)的标准命称。Git 允许你起任何名字,但全世界的程序员都默认用这两个词。 origin - 指向你自己的 GitHub 仓库地址。当你git clone时的远程地址. upstream - 指向原作者(官方)的源码仓库地址。需要你手动添加(

git remote add upstream ...)

基本流程: Fork 官方仓库 → 本地独立分支开发 → 通过 upstream 同步更新 → 合并到自定义分支

-

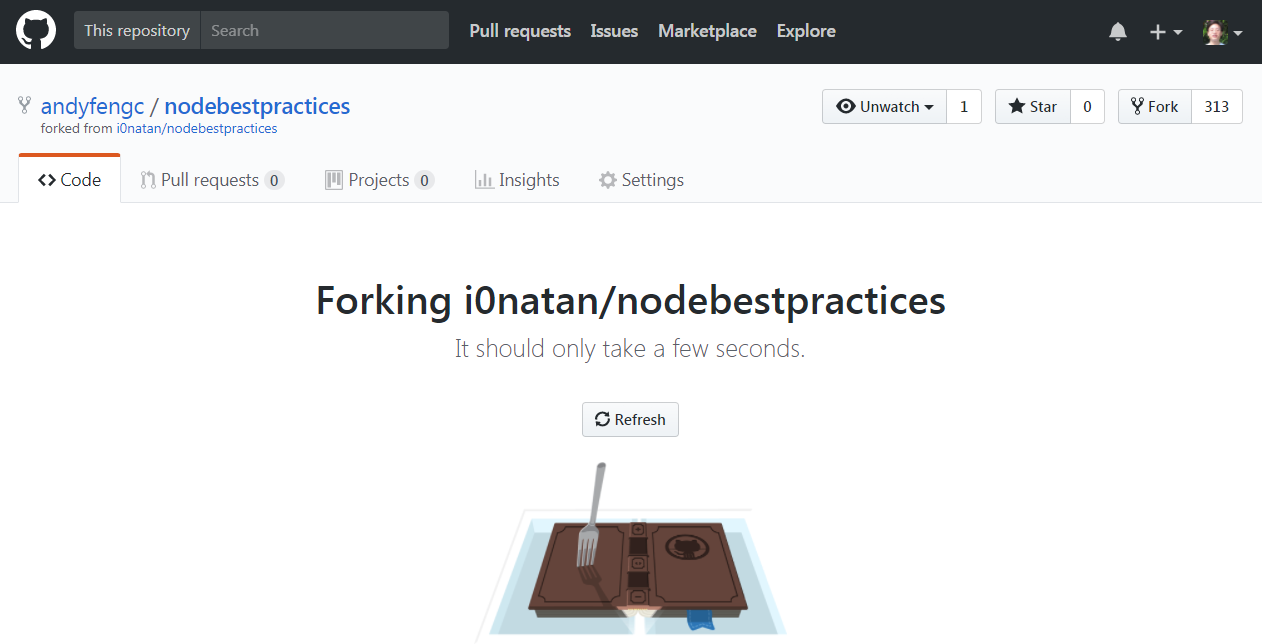

First, we make a fork via the fork button of the project.

这会在你自己的账号下创建一个完全一样的仓库副本(Repository)。

这会在你自己的账号下创建一个完全一样的仓库副本(Repository)。 - 将你自己的那个远程副本克隆到本地电脑上:

git clone https://github.com/你的用户名/项目名.git - 添加上游仓库(Upstream),重要!

此时,你的本地仓库只认识你自己的 GitHub 副本(通常叫

origin)。你需要告诉它原作者的地址(通常叫upstream):# 添加原作者的仓库作为上游 git remote add upstream https://github.com/原作者/项目名.gitWhereas a regular Git workflow uses a single origin remote that points to the central repository, the Forking Workflow requires two remotes — one for the official repository(typically called upstream), and one for the developer’s personal server-side repository(typically called origin).

if our upstream repository has authentication enabled (i.e., it’s not open source), we will need to supply a username

git remote add upstream https://user@bitbucket.org/maintainer/official-repo.git

This requires users to supply a valid password before cloning or pulling from the official codebase.

检查

git remote -v

你应该看到:

origin https://github.com/你的用户名/项目名.git

upstream https://github.com/原作者/项目名.git

- 本地修改与使用

你可以直接在

main分支修改,但最佳实践是创建一个新分支:git checkout -b my-feature # 修改代码... git add . git commit -m "My custom changes" - 同步原作者的更新. 当你发现原作者更新了代码,你想合并进来时:

```

1. 获取原作者的所有更新

git fetch upstream or git pull upstream main

2. 确保你在自己的主分支上

git checkout main

3. 合并原作者的更新到本地

git merge upstream/main

4. 如果你想让你的自定义分支也更新,切换回去合并 main. 如果有冲突,手动解决

git checkout my-feature git merge main

(可选)推送到你自己的 GitHub

git push origin my-feature ```

make a pull request Once a developer is ready to share a new feature, we need to do two things.

-

First, we have to make the contribution accessible to other developers by pushing it to their public repository:

git push origin feature-branchThis merges changes in the origin remote points to the developer’s personal server-side repository, not the main codebase.

-

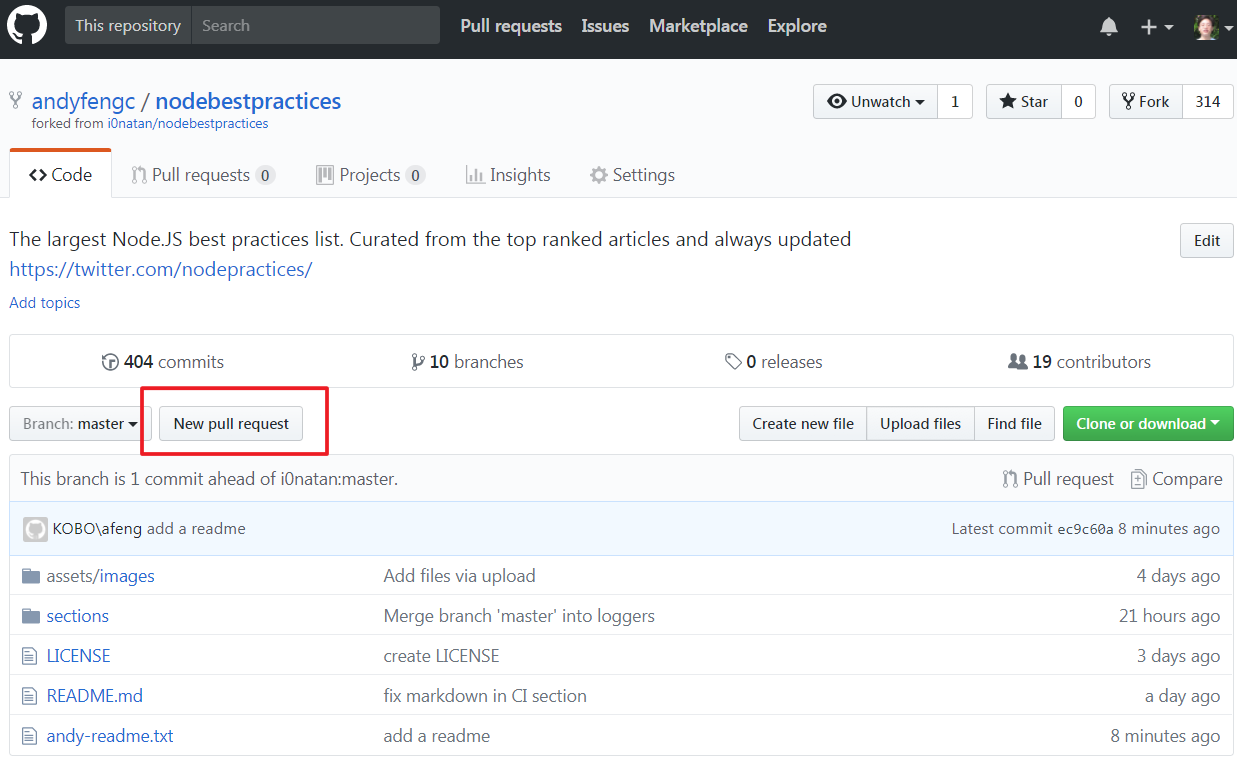

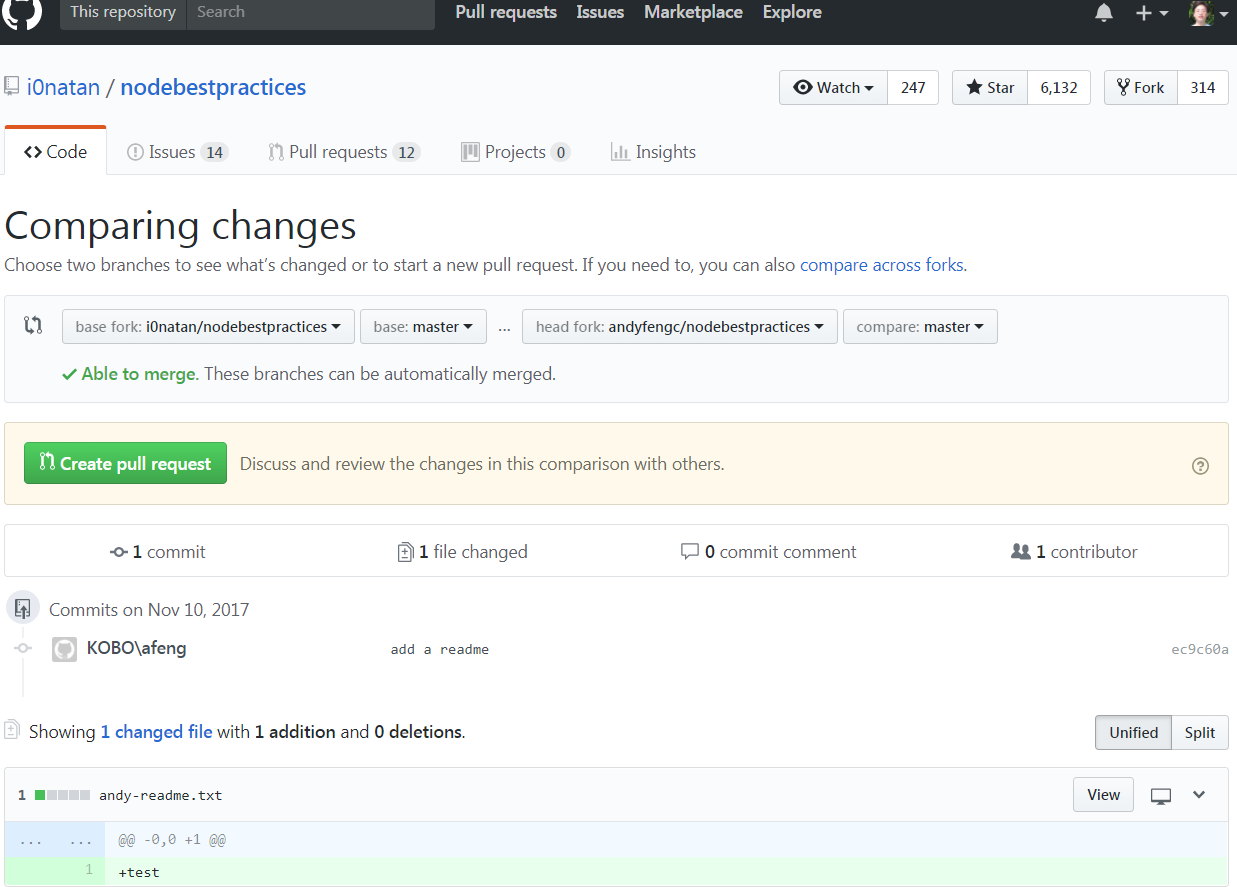

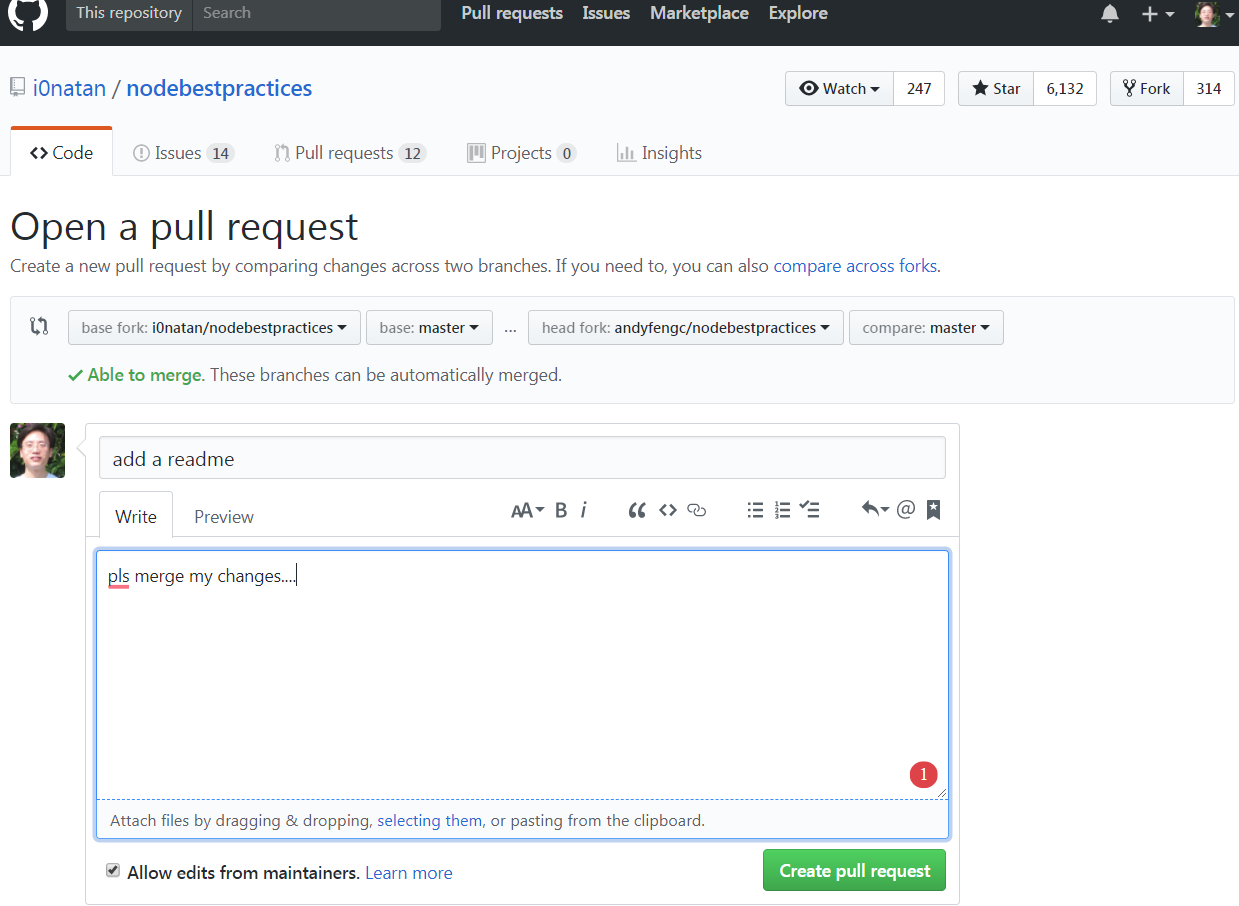

Next, we need to notify the “official” project maintainer that we want to merge the new feature into the main codebase. We can do this by the “pull request” button and it leads us to a form asking you to specify which branch you want to merge into the official repository. Typically, we want to integrate your feature branch into the upstream remote’s master branch.

If I am in a branch of a project, after I made some changes. I send a pull request to the project owner. He receive the pull request and merge my code. Pull request works like an alert to notify the owner it is okay to merge. If I do not send pull request, he can also merge my code.

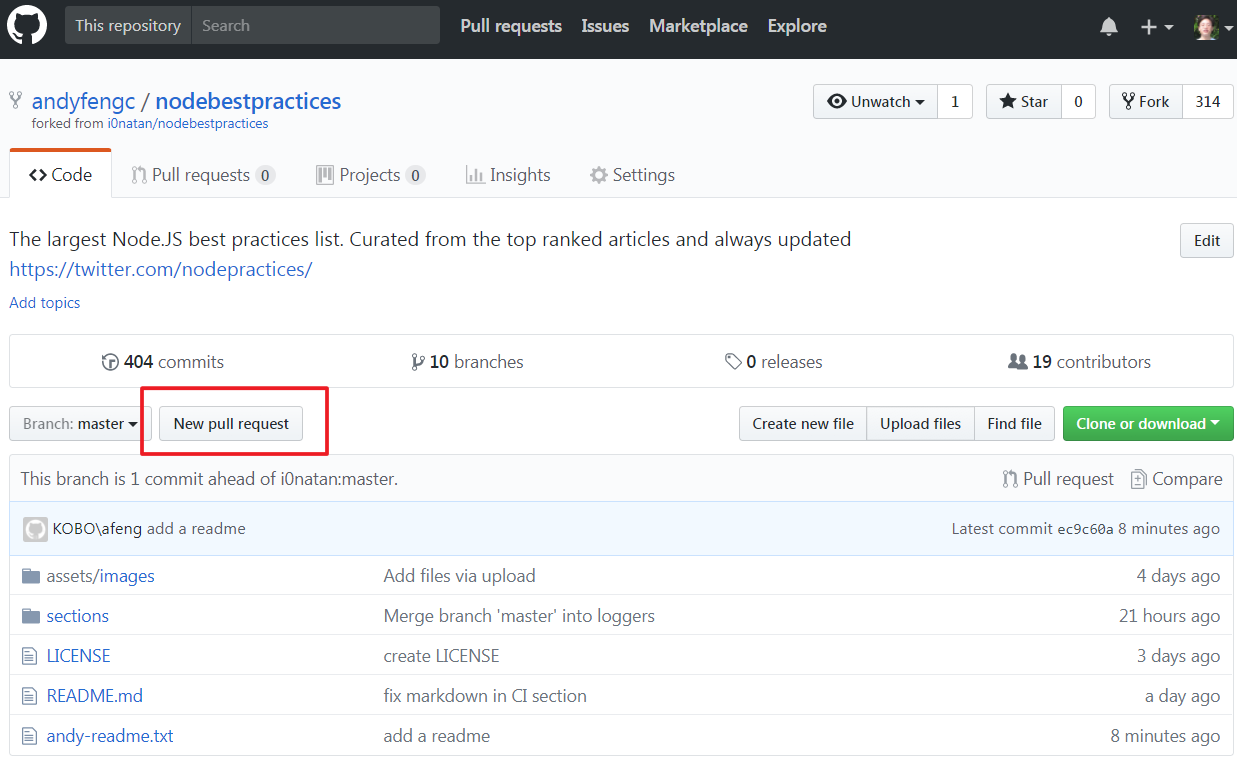

Workflow

Here is how it works:

-

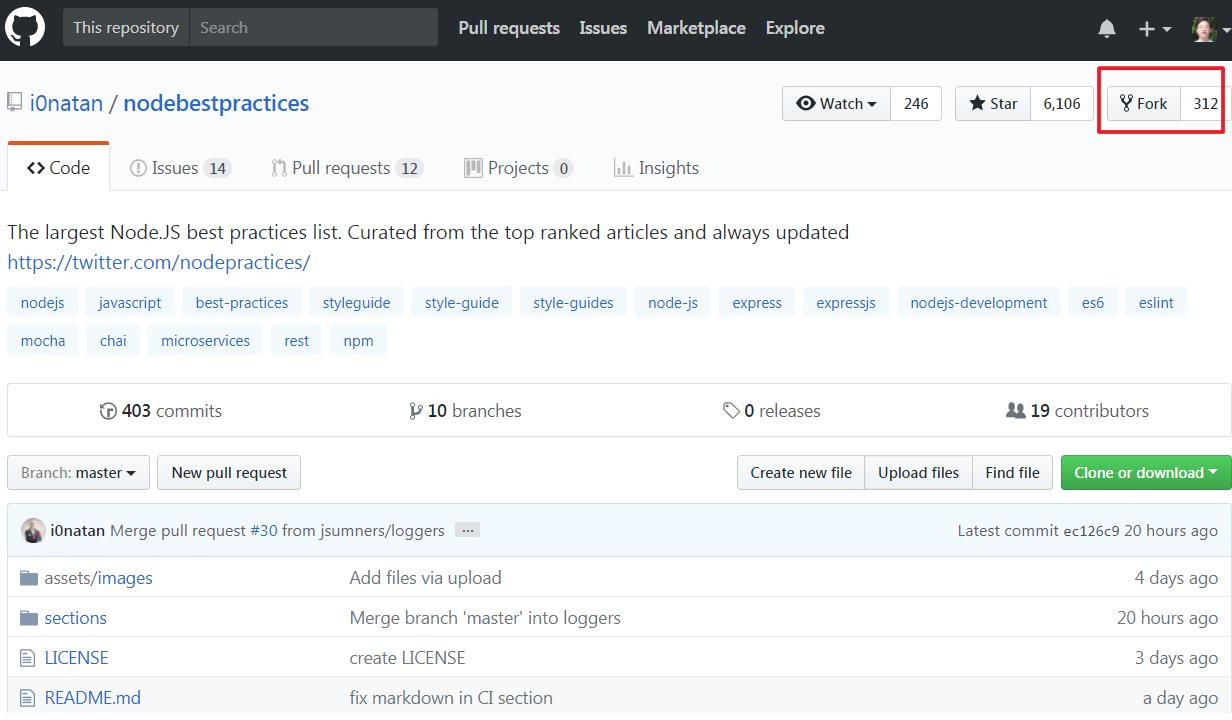

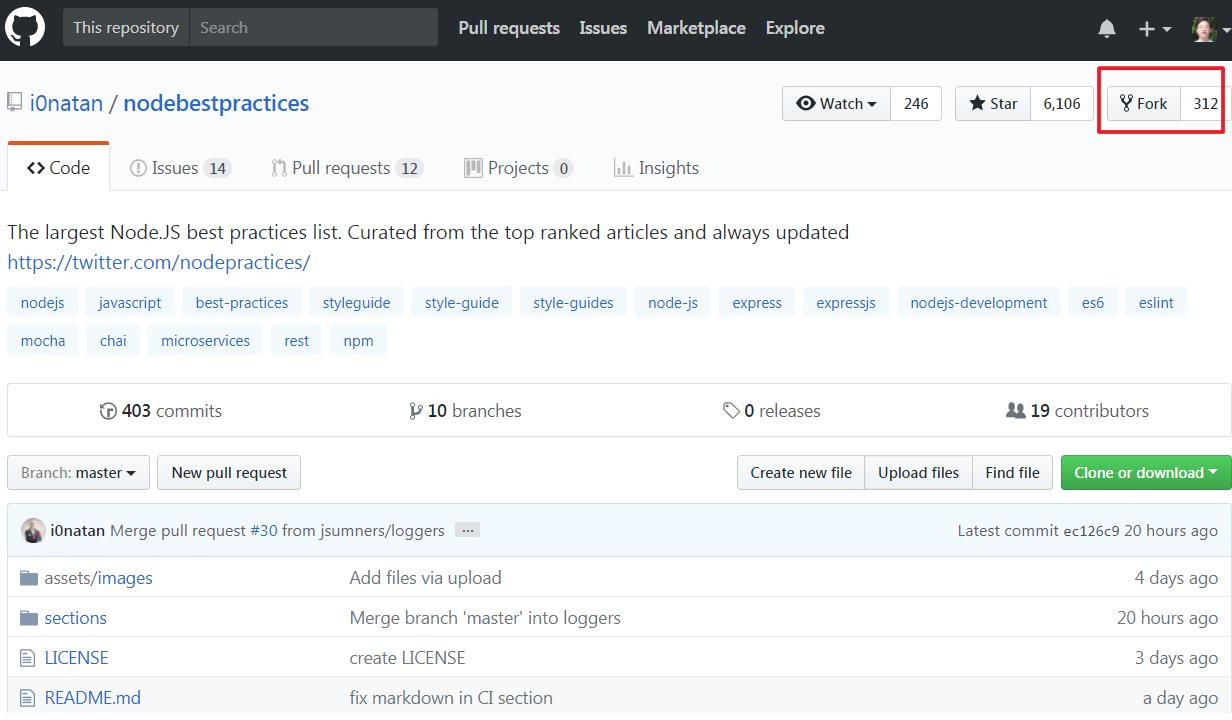

There is an official public repository stored on a server and a new developer wants to start working on the project.

https://github.com/i0natan/nodebestpractices -

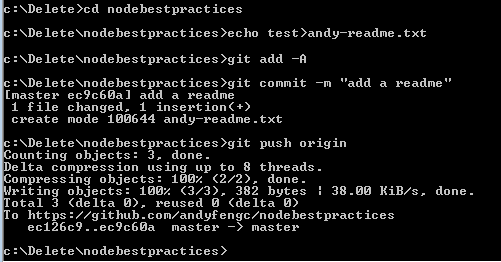

A developer “forks” this official server-side repository. This creates their own server-side copy.

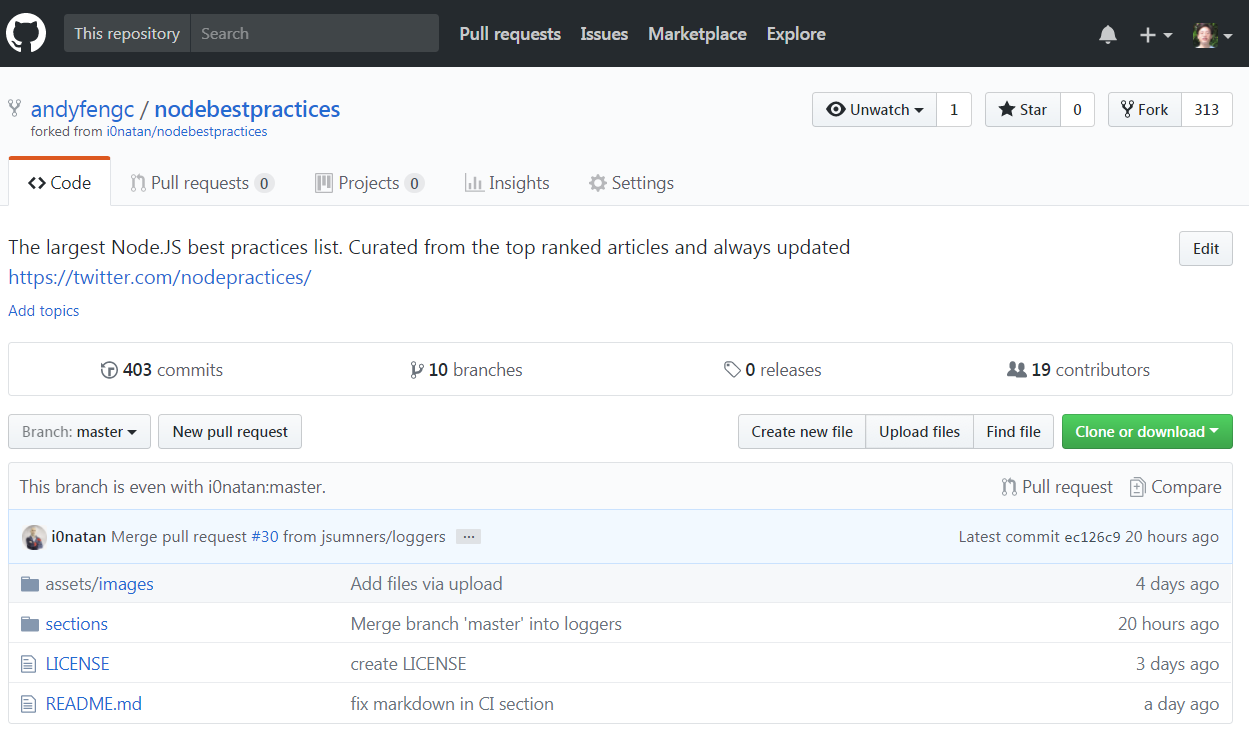

After fork, we have our own repository

https://github.com/myusername/nodebestpractices -

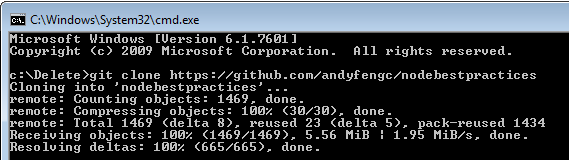

The developer clones the new server-side copy to their local system.

git clone https://github.com/myusername/nodebestpractices

-

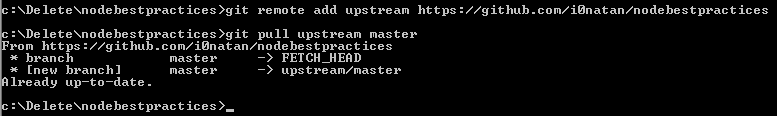

A Git remote path for the “official” repository is added to the local clone. It is a link with the original repo and called upstream.

git remote add upstream https://github.com/i0natan/nodebestpractices -

The developer makes changes on the forked repository as usual.

-

The developer creates new commits for the changes.

-

New changes are pushed to the developer’s own server-side copy.

-

The developer opens a pull request from the new branch to the “official” repository.

Select the desired forked/upstream branches at the top, enter message and submit the pull request

-

The pull request gets approved for merge and is merged into the original server-side repository.

-

The contribution is now part of the project, and other developers pull from the official repository to synchronize their local repositories.

-

The developer constantly grab new updates from “official” repository in order to keep synchronizing with it.

git pull upstream master

fork vs clone

- Forked repositories can be regarded as “server-side clones” and usually managed and hosted by a 3rd party Git service like Github, Bitbucket.

- A “fork” is a “clone” from official repository to remote repository. It happens in server sides.

- A typical “clone” operation is essentially a copy from a remote repository to local repository. It happens from server side from local side.

fork vs branch

- Fork is just another way to share branches between repositories with other developers

- Developers should still use branches to isolate individual features to their own local and remote repositories

- The major difference is how those branches get shared. In the forking workflow, branches are shared between maintainer’s official repository and another developer’s remote repository. In the branching Workflow, branches are shared between one developer’s repositories.

summary

Generally, forks are used to either propose changes to someone else’s project or to use someone else’s project as a starting point for your own idea. The Forking Workflow is commonly used in public open-source projects. Forking is a git clone operation executed on a server copy of a projects repo. A Forking Workflow is often used in conjunction with a Git hosting service like Github/Bitbucket.

A brief steps of Forking Workflow is:

-

We want to contribute to an open source library

-

We create a fork of the repo via a Git hosting service i.e. Github, Bitbucket

-

We use git clone to get a local copy of the forked repo

-

We create a new feature branch in your local repo then work on it

-

Work is done to complete the new feature and git commit is executed to save the changes

-

We then push the new feature branch to our remote forked repo

-

We use Git hosting service to open up a pull request for the new branch against the original repo

Stash

introduction

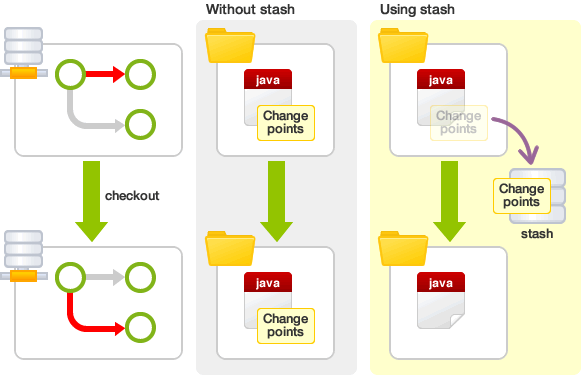

Stash temporarily store changes we have made to your working copy so we can work on something else, and then come back and re-apply these changes later on. stash is a great feature for us to work on multiple branches.

Problem

Typically, we create a new branch for each new requirement. After development work is done, we merge the changes back to trunk branch. However, we sometimes have to create new branch or switch to another branch for new urgent tasks before the work of current branch is completed.

There are some issues for that:

- don’t commit changes -

- Case 1: If we switch to another branch with uncommited changes of new added files in current branch, these uncommited changes will also be carried to the new branch that you switch to. Changes that our next commit will be commited to the newly switched branch.

-

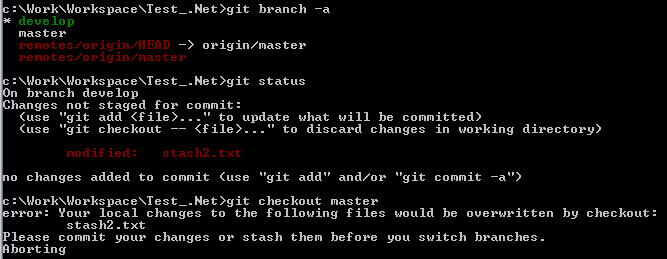

Case 2: If we try to switch to another branch with updated files and we already got another branch updated same files, Git doesn’t allow us to switch between branches. The reason is Git finds a conflict between the files from the newly switched branch and the uncommited changes from the current branch. Therefore, we are required to commit or stash changes first before switching branch.

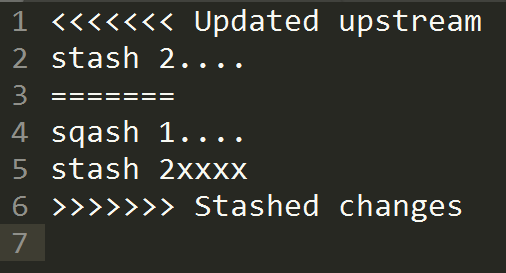

e.g. We have “stash2.txt” commited new changes in master branch. Also, we currently in develop branch and got “stash2.txt” updated. We cannot switch back to master branch.

- commit changes - If we commit uncompleted changes in current branch, then create new branch and start working on, we might include broken code in current branch.

Obviously, we should always keep changes within current branch and find a good way to cache changes if we prefer not to commit dirty changes when switching branches.

Solution

Stash is a solution for that. Stashing likes a a drawer to store uncommited changes temporarily. It allows us to put aside the dirty changes in your working tree and continue working on other things in a different branch on a clean slate.

Uncommited changes that are stored in the stash can be taken out and applied to the original branch and other branches as well. It helps us to cache changes and kind of “revert” changes to last commit of current branch. Then we can switch branches safely.

workflow

-

we are working on one branch(develop) and updated “stash2.txt” file

-

we got “stash2.txt” commited changes in another branch(master)

-

For some reason, we have to create or switch new branch. We prefer not to commit “stash2.txt” file and choose to stash it.

-

stash our changes

git stashCurrent branch will revert to last commit.

-

Display stash list:

git stash list -

switch to new branch, do some work

git checkout -b <another-branch> -

pop out changes from git cache. Git will append changes for same files.

git stash popWith this command, it deletes that stash. Please note that the stash is shared within all branches. Which branch we are currently on, the changes will be popped to that branch.

-

Solve conflicts issue if has any. commit and merge changes to trunk branch

Other commands:

Apply most recent stashing without removing

`git stash apply`

apply specified stashing

`git stash apply stash@{stashing_index}`

Remove most recent stashing

`git stash drop`

remove specified stashing

`git stash drop stash@{0}`

Clean out the stashing stack

`git stash clear`

Merge, Rebase, Squash

In Git, there are two main ways to integrate changes from one branch into another: the merge and the rebase.

Merge

merge is the easiest option to merge changes within branches

merge another branch into current branch

git merge <another-branch>

git merge --no-ff <branch>

Merge the specified branch into the current branch, but always generate a merge commit (even if it was a fast-forward merge). This is useful for documenting all merges.

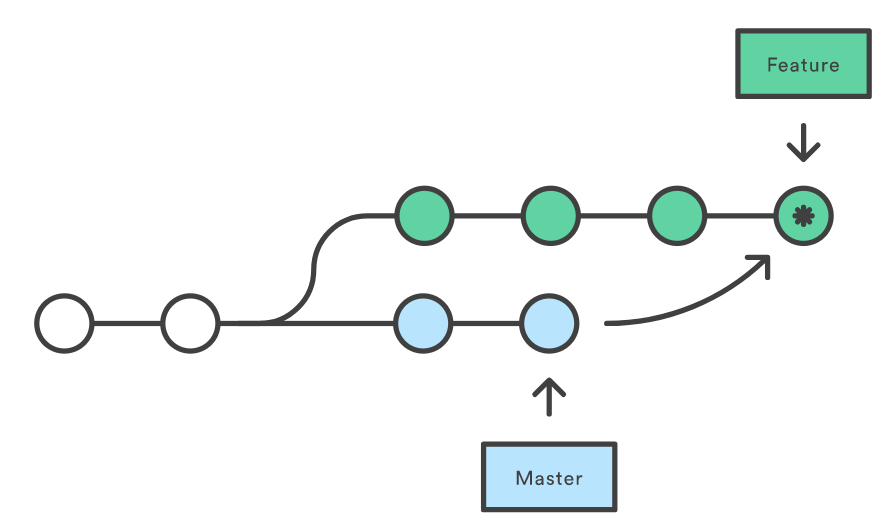

e.g. We have a feature branch and hope to merge changes to master branch:

git checkout master

git merge feature

Or, we can condense this to a one line:

git merge master feature

This creates a new “merge commit” in the feature branch that ties together the histories of both branches, giving us a branch structure that looks like this:

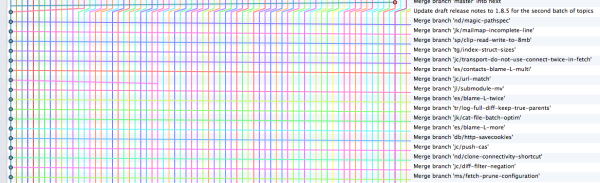

However, each merge generates a certain merge point when we incorporate changes. If we have many branches and merge happens very often, this can pollute our master branch’s history quite a bit.

git checkout feature

git rebase master

Rebase

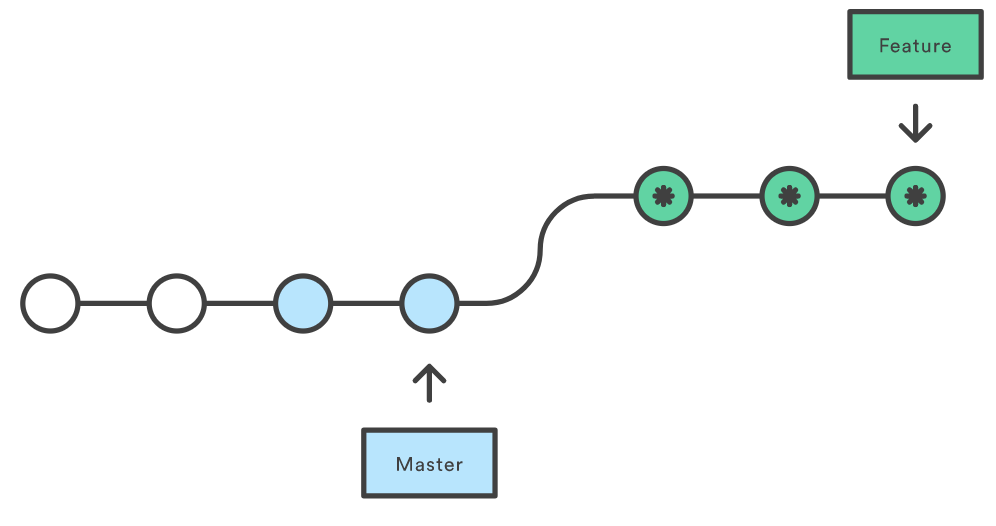

As an alternative to merging, we rebase the feature branch onto master branch using the following commands:

git checkout master

git rebase feature

This moves the entire feature branch to begin on the tip of the master branch by incorporating all of the new commits in master. Instead of creating a merge commit point, rebasing re-writes the project history by creating brand new commits for each commit in the original branch and fast-forwards the commit. Rebasing is essentially fast-forward merge.

The major benefit of rebasing is that you get a much cleaner project history. It eliminates the unnecessary merge commits created by git merge. However, we lost the context provided by merge commit.

In practice, if our team members pushed changes prior you in remote branch. We have to use git pull to grab those changes. By default, git use merge option to incorporate changes. In this case, a new merge commit point will be created. We can use rebase option to fast forward to new changes:

git pull --rebase

In most cases, we choose rebase policy for a clearer git history for code review.

Squash

Squash option can produce a “squashed” commit. It compress multiple commits into one single commit and simplify git history. Squash is not a command but an option and it is used together with merge or rebate.

Merge + Squash

e.g. we squash all commits of feature branch and merge to master branch

git checkout master

git merge --squash

After squash, there is only one commit from feature branch merged to master branch

rebase + squash/fixup

e.g. we hope to merge git log

a

b1

b2

b3

to

a

b

-

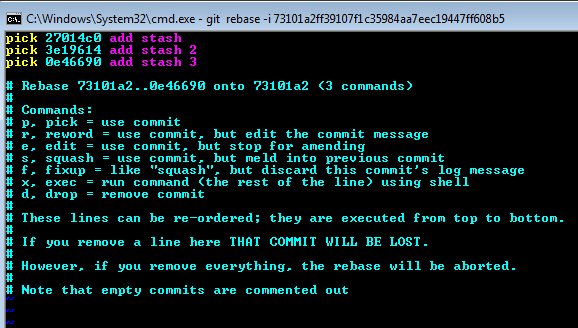

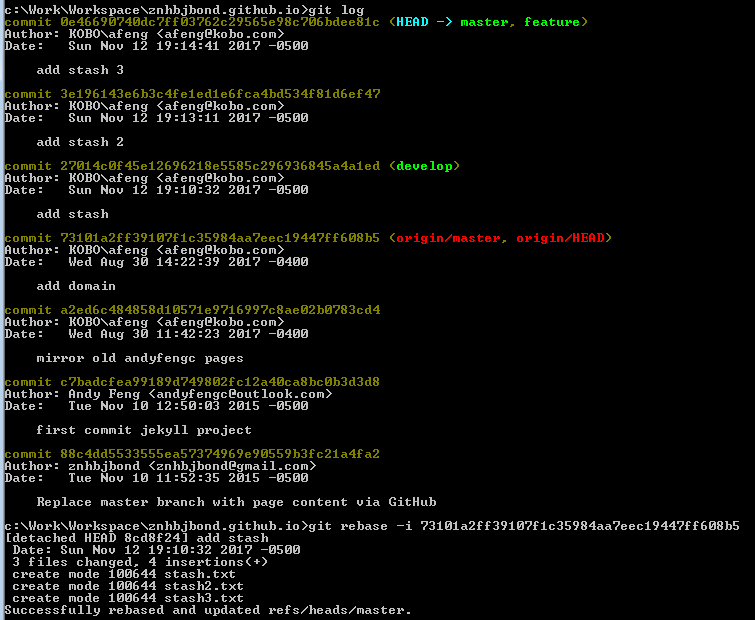

check commit history via

git log -

enable rebate interactive editing

`git rebase -i

-

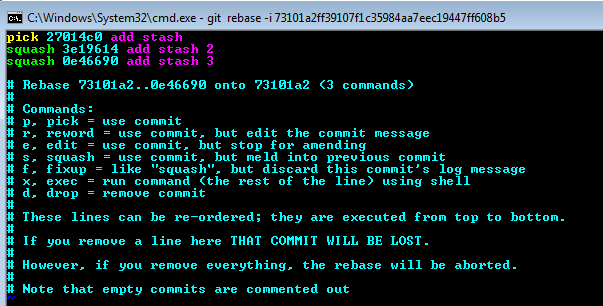

edit the instructions to modify b2, b3 from “pick” to “squash”

- pick: commit

- squash: meld into previous commit

modify

to

esc > :wq > save and exit

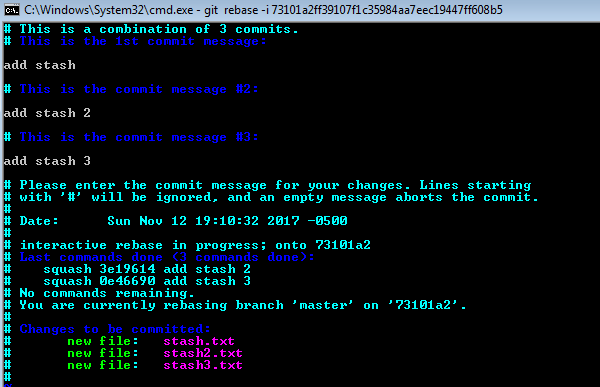

-

enter new commit message

Here is the complete commands

After squash, the rebate will only keep one commit. Basically, squash option let us to squash commits backwards until recent “pick”.

fixup option like squash, the only difference is squash keeps all commits’ messages but fixup discard all previous commits’ messages.

cherry-pick

对于多分支的代码库,将代码从一个分支转移到另一个分支是常见需求。

这时分两种情况。一种情况是,你需要另一个分支的所有代码变动,那么就采用合并(git merge)。另一种情况是,你只需要部分代码变动(某几个提交),这时可以采用 Cherry pick。

git cherry-pick命令的作用,就是将指定的提交(commit)应用于其他分支。

git cherry-pick

该命令就会将指定的提交commitHash,应用于当前分支。这会在当前分支产生一个新的提交,

git cherry-pick命令的参数,不一定是提交的哈希值,分支名也是可以的,表示转移该分支的最新提交。

e.g. 代码仓库有master和feature两个分支。

a - b - c - d Master

\

e - f - g Feature

现在将提交f应用到master分支。

切换到 master 分支: git checkout master

Cherry pick 操作: git cherry-pick f

上面的操作完成以后,代码库就变成了下面的样子。

a - b - c - d - f Master

\

e - f - g Feature

转移多个提交

Cherry pick 支持一次转移多个提交。

git cherry-pick

如果想要转移一系列的连续提交,可以使用下面的简便语法。

git cherry-pick A..B

它们必须按照正确的顺序放置:提交 A 必须早于提交 B,否则命令将失败,但不会报错。

demo

-

Create a new branch from master

git checkout -b audit-new master -

merge specific commit hash

git cherry-pick 5e7ea3c -

Fix conflicts

git add . git commit -m "message..." -

move on merging next commit

git cherry-pick 806a998

Fix conflicts

git add . git cherry-pick –continue git cherry-pick 806a998

And so on

References

-

Previous

ASP.NET WebApi file upload implementation -

Next

Best practice of using Git to integrate teamwork